Is your SOX approach based on risk or capacity? Are you sure?

highlights

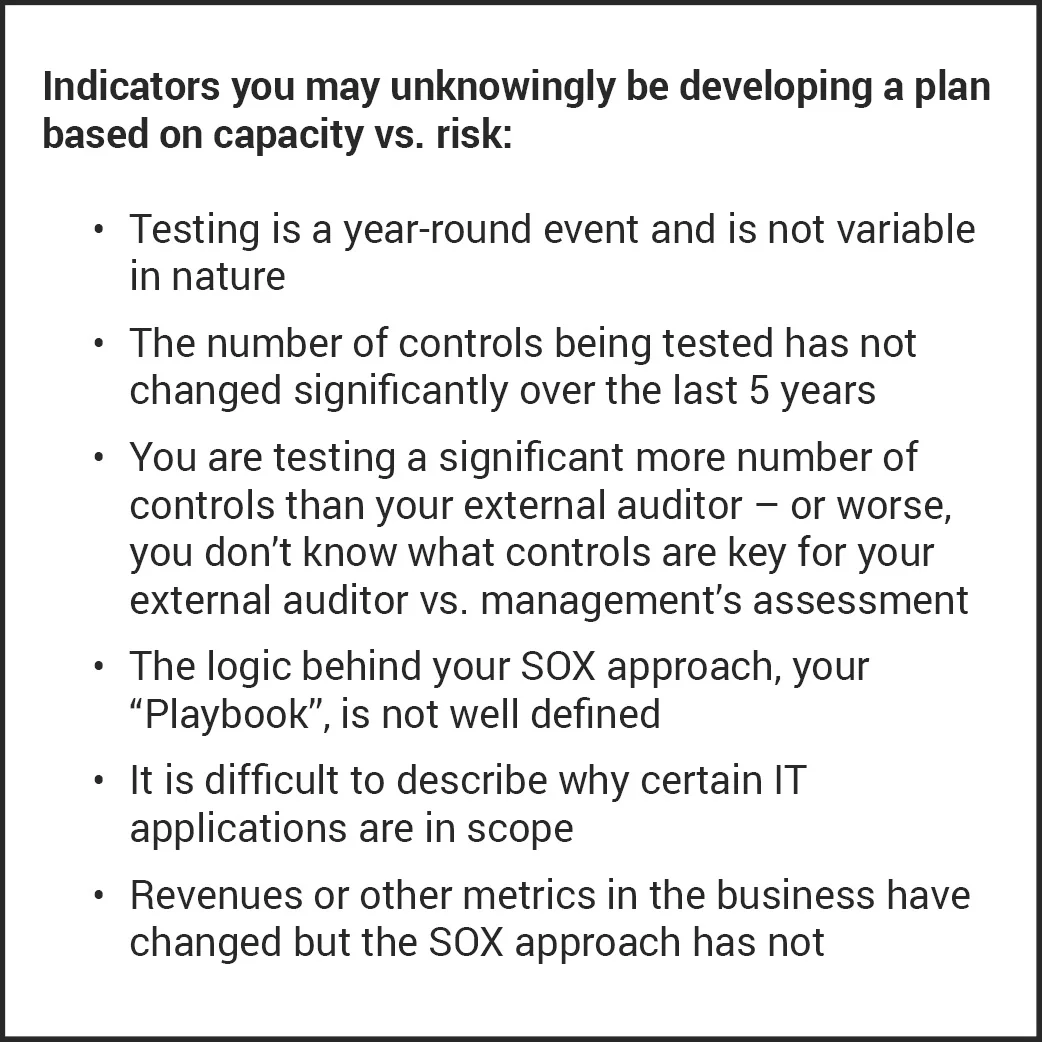

- A surprising number of organizations still base their SOX approach on the capacity of their team (albeit unknowingly) versus a formalized process based on risk

- Despite an evolving regulatory environment, SOX compliance is a highly repeatable process that requires a formalized “Playbook” and clear definition of why you are doing what you are doing

- Alignment with external audit is critical to improving your approach and increasing efficiency

- Executive management and the audit committee should not just understand your SOX approach, but clearly understand the logic behind that approach

For over a decade organizations have been performing assessments of their internal control environment in an effort to comply with Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX). And for over a decade I have been fascinated by the number of organizations that develop their SOX program based on the capacity and skillset of their internal auditors versus risk. In the early days of SOX compliance defining your program, performing control testing and aligning with your external auditor was an absolute full time effort – it was “all hands on deck” plus we need to hire 12 more hands! However, as time passed, Auditing Standard 2 (AS2) was replaced with Auditing Standard 5 (AS5) and organizations generally learned to become more efficient with their SOX compliance program. In many cases the risk management strategy of the organization depended on it – we need internal control specialists available to review other high risk areas of the organization not just our financial controls. With this context, it is remarkable that a significant number of organizations are still developing a SOX compliance program based on the capacity of internal control testers versus risk. I would argue that a large majority of organizations are not developing their SOX programs based on capacity, however, far more organizations than one would imagine, or expect (I would suggest 1 in 5 based on my experience), still develop an approach based on the number of people they have available to perform testing.

What does it mean to develop a plan based on capacity vs. risk?

This is a concept that is difficult for many organizations to admit occurs. It simply means that the nature and frequency of control testing to support management’s assessment of internal controls is based on the number of people available to test controls versus a real risk based scoping and testing approach. For example, I worked with a Fortune 50 automaker that had over 120 resources in their global Internal Controls function that was responsible for performing SOX control testing. Their SOX testing approach (knowingly or otherwise) was based on making sure all 120 resources were busy at all times thus the following occurred:

- 3-4 cycles of testing for all controls occurred rather than a more efficient 1-2 cycle testing approach. Control testers needed to stay busy so control testing occurred all year.

- Controls were more easily introduced into the control environment as “key” controls. If a program is not based on risk it becomes increasingly difficult to evaluate new controls by any other method than “do we have the time to test it?”. Without fail, you will see more key controls in this environment than programs taking a risk based approach.

- It’s easier for a location, process or system to be deemed “in-scope” if you have the capacity to test controls at that location. While a well-defined evaluation of risk should ultimately be the defining factor I often see the availability of resources make the determination as to whether a location should be part of management’s assessment.

The management team developing the SOX testing approach needs to develop a plan that will keep everyone busy so that might mean adding additional cycles of testing, evaluating more controls or adding processes to scope. Of course, management would not believe what I’m describing here. Management would argue their capacity is based on the risk of the organization, thus, everything they are doing is “risk based”. The problem is when you are planning to capacity (whether you admit it or not) there’s very little formality used to define risk, what is in scope and what controls are key and why. I believe this is because, regardless of what a formal risk based scoping process tells them, management knows they need to keep everyone busy.

Why does this still happen?

The first priority of executive management and the audit committee is to “keep us out of trouble” – In most organizations where the SOX scope is not aligned to risk you hear this reasoning. However, if you listen carefully to management and the board they are not saying “keep us out of trouble by testing things that don’t matter and spending extra money.” They are asking you to “keep us out of trouble”, which means performing a well thought out, risk based scoping process and spending your time on the locations, processes and controls that matter most to the organization. It means clearly understanding why you are doing what you are doing. Many organizations are “conservative” from an internal controls perspective, which doesn’t mean all controls need to be tested as part of your SOX compliance program. Management may still want all controls to be tested but that does not mean they need to be “key” SOX controls requiring a stringent testing cycle.

People do what’s comfortable – Once an organization builds the habit of adding locations, processes, systems and controls into scope without a formal process it is difficult to stop the cycle. Testing SOX controls becomes a routine and many internal auditors or other testers grow comfortable with a routine. They know what they’ll test each year, when they’ll be tested and who they’ll be working with. This is very comfortable and psychologically many of us like this comfort. In some cases, internal auditors and other testers do not have the skillset to shift their focus to emerging risk areas since they have been trained exclusively to test SOX controls. Change means declaring something that was important last week “not as important”. It means having to convince executive management and the board you will continue to “keep us out of trouble”. These things are all hard and sometimes saving money, re-positioning resources to more valuable activities and being efficient take a back seat to being comfortable.

External auditors don’t mind it – I have yet to see an external auditor proactively tell an organization they are testing too many controls (although I’m told it happens). In general, I believe external auditors gain comfort when they see management assessing more controls, whether those controls are the right ones of not. External auditors must be efficient, their business model depends on it, so they take a very formal risk based approach when developing their scope for internal control testing. If your external auditors say they are “relying” on all those extra controls that you designate as “key” (and they don’t) I would challenge this assertion. Often times “relying” means it provides the external auditor with a “warm and fuzzy feeling”…and “warm and fuzzy feelings”, while heartwarming, can be very expensive.

Why does it matter?

Effectively answering this question has been one of the biggest challenges when working with an organization to change. After all, if your ultimate goal is SOX compliance, you are most likely achieving it.

Your valuable internal control resources are needed elsewhere – Team members with a deep understanding of internal control have a unique skillset. Whether it’s performing an internal audit of an emerging risk area, or working as part of a process improvement team to increase the efficiency of a business process, internal controls is a required skillset. Organizations change today faster than ever and resources need to be focused on more than SOX.

SOX compliance is too costly – Simply put, if your plan is actually based on capacity more than risk you are spending too much money. That “money” comes in the form of additional resources to test (primary expense) and additional time from business resources to document controls, etc. In most organizations, it will make sense to re-position resources to help in other areas of the business given their skillset rather than reducing resources.

If everything is important, is anything really important? – Finally, if your approach is based on capacity rather than risk you tend to test more controls than necessary – everything becomes important. In this scenario the controls that are truly most important receive the same attention as controls within a process that may not be as critical to your financials. Thus, thoughtful focus on the areas of highest risk, which is what will really “keep us out of trouble” is neglected in favor of a everything being “kind of important”. This actually creates greater risk to the organization and should be a concern for management.

What can organizations do about it?

Clearly define your “SOX Playbook” – Despite an evolving regulatory environment executing a compliance process like SOX is a highly repeatable process. Therefore, I recommend organizations take the time to define a “SOX Playbook” that clearly defines the following elements:

- The process management follows to perform a qualitative and quantitative risk assessment, which defines which processes and locations are in scope.

- The process management follows to define the IT applications in scope

- The process management follows to assign a level of risk to each control and how risk drives the overall testing approach (nature, timing, extent)

- The process management follows to define a reliance strategy with their external auditors

- The process management follows to identify, report and measure issues

Once a Playbook is in place management may still choose to make conservative decisions related to the SOX program - but at least those decisions will be intentional supported by logic.

Align with your external auditors – As you develop your Playbook it is important to have your external auditors at the table. They should not drive your approach but they should be aligned so a) efficiencies can be driven and b) you have a supportive party when the approach is presented to the audit committee. It’s critically important that your external auditors understand why you are doing what you are doing.

Sell your new approach internally – I have found it surprising how many audit committees and members of executive management do not understand how management’s SOX scope was developed. It’s important that management and the board understand your risk based approach, why certain locations and processes will be in scope and why others won’t. If they do not understand your “why” they will certainly not feel comfortable you will “keep us out of trouble”. There will be concern when locations that have historically been in scope (with only informal logic) are no longer in scope. Bringing transparency and logic to your decisions with ensure the board and management gain comfort in your new approach.

in Conclusion

Despite the fact SOX compliance has become a routine process for many organizations there remains a tremendous opportunity to challenge traditional approaches and drive efficiency. Organizations should ask themselves hard questions, and if they aren’t completely comfortable with the answers, the steps described here can lead to significant efficiencies for a very reasonable amount of effort.